Refugee status of Rohingyas and India’s decision to send them back: An Analysis – Part 1

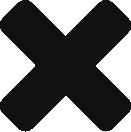

The World Migration Report 2018 states that 3.3% of world’s population comprises of international migrants i.e. 244 million people approximately. The report published by the UN’s International Organisation for Migration (IOM) also estimates that 6% of those 244 million are “Refugees”. Clearly, the IOM itself appreciates and strikes a difference between “migrants” and “refugees”. Another statistic that merits our attention from this Report would be the fact that India accommodates the largest number of international migrants in Asia (See Figure 1; Dark blue represents immigrants and light blue represents emigrants) and globally it ranks 12th in top destinations for international migrants and ranks 25th top asylum destination for refugees. Over the years UNHRC has recognised India as one of the most conducive host countries where refugees are given free public services including health and education.

Figure 1. Top 20 Asian Countries that accommodate international migrants (Source WMR 2018).

Above facts beg the question as to why India’s position with respect to Rohingya community is in the crosshairs of the international media. What is it about India’s position which the international media claims is at loggerheads with established principles of treatment of refugees, if at all the Rohingyas indeed qualify as refugees? In order to answer these questions, it becomes imperative to understand the first principles that apply to treatment of a group as refugees and the obligations of countries towards refugees.

Who is a Refugee?

Clause 2 of Article 1A, 1951 Convention ‘Relating to the Status of Refugees’ says that the term “refugee” shall apply to any person who: “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his habitual residence is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to return to it”.

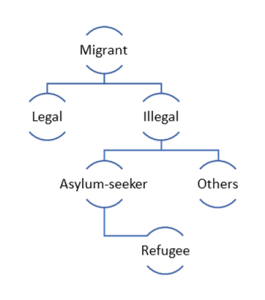

Figure 2: Classifying Migrants

Emphasis is on the ‘fear of persecution’ and ‘inability or unwillingness to return to the country of his nationality’.1 It is important to point out that the status of a Refugee is granted by the host State and is not bestowed upon a person ipso facto. This is not a mere technicality but is meant to preserve the sovereign rights of a host state to determine whether a person or a group is entitled to be treated as a refugee. Importantly, this definition implicitly recognises the distinction between a refugee, an asylum-seeker, an illegal migrant, and a foreigner. ‘Asylum-seeker’ is a general term that refers to anyone who seeks international protection.2 It is an internationally recognised human right3 to seek asylum, and for that purpose a person/s cannot be prevented from entering a foreign territory. A migrant however, is someone who has travelled to another nation not particularly because of the fear of persecution in his/her home country but for any other reason like work, education etc. A migrant can return home; there is no inability to go back, however unwillingness might exist. Whether a migrant is ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’ would depend on the migration laws of the destination State.4

Another term sometimes used interchangeably with a migrant i.e. an alien/foreigner. An alien/foreigner would be a person who does not have the host nation’s citizenship.5

It is clear from the above that the category that comes closest to the status of a refugee is an asylum-seeker. However, an asylum-seeker is entitled to be treated as a refugee only when the host State bestows him with that status. According to provisions of the 1951 Convention, a signatory host State as a soveriegn is free to formulate its domestic policies and procedures for granting legal recognition to refugees and facilitating them.

State obligations towards a Refugee

The 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol 6 form the core of international refugee protection regime. These instruments define who shall be granted the status of a refugee and the kind of legal protection and assistance such persons are entitled in the signatory States.7 Provisions of the 1951 Convention expressly create specific obligations on contracting/signatory States. However, certain provisions are recognised internationally as forming a part of customary international law, which is equally binding on non-signatories to the convention as well, such as India. The principle of Non-refoulment under Article 33 is one such provision that says:

“No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

This principle, however, is subject to the following exceptions given in the Covenant itself:

(i) Article 1(F) – “The provisions of this Convention shall not apply to any person with respect to whom there are serious reasons for considering that: (a) he has committed a crime against peace, a war crime, or a crime against humanity, as defined in the international instruments drawn up to make provision in respect of such crimes; (b) he has committed a serious non-political crime outside the country of refuge prior to his admission to that country as a refugee; (c) he has been guilty of acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.”

(ii) Article 9 – “Nothing in this Convention shall prevent a Contracting State, in time of war or other grave and exceptional circumstances, from taking provisionally measures which it considers to be essential to the national security in the case of a particular person, pending a determination by the Contracting State that that person is in fact a refugee and that the continuance of such measures is necessary in his case in the interests of national security.”

(iii) Article 32(1) – “The Contracting States shall not expel a refugee lawfully in their territory save on grounds of national security or public order.”8

(iv) Article 33(2) – “The benefit of the present provision may not, however, be claimed by a refugee whom there are reasonable grounds for regarding as a danger to the security of the country in which he is, or who, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of that country.”

Apart from above exceptions to the principle of non-refoulement pertaining to national security and public order, another procedural exception is that refugees who gain protection under any agency other than the prescribed UNHCR9 will not be covered under the 1951 Convention. What is important to note is that the Convention also casts obligations on a refugee towards the host State, which includes the obligation to conform to the laws and regulations of the host State as well as the measures taken to maintain law and order.

It is in the above legal backdrop that India’s position with respect to Rohingyas must be examined.

End of Part 1

- The term also includes a person of no nationality unless the case falls into exceptions and exclusions explicit under the 1951 Convention or the refugee status has ceased.

- It may be a person who has applied for the refugee status but has not yet received the same, or someone who was denied the status.

- Article 14(1) of Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948.

- A migrant can be classified as illegal for the following reasons mainly:

(a) Illegal entry i.e. illegal crossing borders to enter a foreign nation;

(b) Entry in absence of legal documents or using false documents;

(c) Entry using legal documents but when information provided in those documents is false;

(d) Overstaying i.e. after expiry of their visa or residence permit;

(e) Breaching the conditions of residency;

(f) Loss of legal status due to their own acts or omissions.

- The legality of his/her stay or residency would again depend on the citizenship laws of the host country, consequently the rights accrued to them. The difference in the usage of these terms is circumstantial.

- The 1951 Convention was initially intended to protect European refugees in aftermath of World War II; the 1967 Protocol expanded its scope to rest of the world.

- The 1951 Convention being the primary instrument also finds support in instruments of international humanitarian law like Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, 1984 Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 1966 Convention on Civil and Political Rights and other regional instruments. The 1969 OAU Refugee Convention in Africa, the 1984 Cartagena Declaration in Latin America and the development of a common asylum system in the European Union

- Sub-clauses 2 and 3 of this Article mandate that the decision to expel a refugee on grounds of national security and public order should be taken in accordance of due process of law (unless compelling reasons of national security preclude) with the asylum-seeker having rights of appeal before an appropriate forum. The provision also says that the contracting States shall allow refuge to such a person for a reasonable period to seek legal admission into another country. The contracting States have the right to apply reasonable restrictions during that period and such internal measures as they may deem necessary.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees is the authority assigned powers to implement provisions of the 1951 Convention as pronounced by its preamble and under Article 35. Article 1(D) of the Convention precludes persons receiving protection or assistance from organisations other than UNHCR. Such as refugees from Palestine who fall under the auspices of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).