Of panels and politics – An unfinished battle for the Western Ghats II

The previous piece briefly discussed the resistance that the Gadgil report had faced then and that it continues to even now, from various quarters. Continuing from there, in this piece we discuss the politics around the Western Ghats (WG) reports, how states are shirking off their responsibility and the impact of this destructive ignorance on this biodiversity hotspot of India.

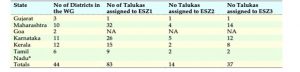

The major takeaway from the Gadgil Report (GR) was primarily that it stressed that a uniform approach could not be employed for the entire WG, and instead, a layered approach was required for regulating development and conservation activities in the region. GR divides the entire region with the most significant region labelled as Ecologically Sensitive Zone I (ESZ 1), followed by a moderately significant– ESZ II and the less significant area as – ESZ III. Given that the Western Ghats are an ecologically vital region, an ambitious 75% of the forest area was treated as that of ‘high’ or ‘highest significance to preserve’, with about 37% set to be declared ‘ecologically fragile’. The table below shows the assignment of various Western Ghats districts to ESZ1, ESZ2 and ESZ3 by the GR.

Image source: Understanding the Report of WGEEP – Kerala State Biodiversity Board

The GR recommended that within these designated ecologically sensitive areas, all types of mining and extraction activities, thermal power plants, polluting industries and water-intensive industries would be prohibited due to their environmental and social impact. Existing mines with environmental clearances were sought to be phased out over the subsequent five years, with a 25% reduction of mining activity per annum, starting from the issue of final notification or on the expiry of the existing mining lease, whichever was earlier. The thrust of the report was that people should have an appropriate role in conservation and development related decisions taken at the local level – Gram Sabhas or alike bodies should be able to pass resolutions on the ecological sensitivity of the respective areas. It was recommended that local communities get to decide whether their areas should be deemed ecologically sensitive zones and in what zone specifically, relegating all powers of conservation to the grassroot level.

Church joins the opposition

Newfound opposition by the Church and its machinery in Kerala strengthened the opposition to the Report. The GR had stressed that local communities and bodies should be empowered to decide what activities would be permitted and/or regulated in each of the zones, which threatened the illegal Church planting and/or encroachment activities in forest areas. A vehement opposition to Gadgil’s Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP) report came from Kerala, in particular from the Syro-Malabar Church (along with certain mining/quarrying lobby and interest groups) which even rallied political leaders in its favor. The battleground was mainly the district of Idduki, where Christians form a significant majority of the electorate, about 43.42% of total population according to the 2011 census.

The GR included 14 taluks in the State to be in the highest ecologically significant zone, of which four out of the five taluks in Idukki – Thodupuzha, Udumbanchola, Devikulam and Peerumedu – were demarcated as ecologically sensitive zones (ESZs). The Kasturirangan committee report, which replaced the Gadgil report, demarcated 123 villages identified as ecologically sensitive areas (ESAs) in Kerala, out of which forty-eight villages were in the Idukki district – and unsurprisingly, a vocal opponent was diocese of Idukki and the Hill Range Protection Council, an allied organisation.

When the report was made public, almost a year after its compilation, the Syro-Malabar Church in Kerala strongly objected to the recommendations of Gadgil’s report, terming it as part of an international conspiracy to allow foreign countries and big companies to exploit the masses by pushing them back by two centuries on the pretext of environmental protection. The claim was that these recommendations were “anti-people”. Though the report said nothing about evicting farmers and locals from small tracts of land in these sensitive areas, the Church and political outfits propagated against the Report, and framed it as an anti-farmer, anti-poor ploy to evict the local Christian residents.

The Church’s hopes were again dashed by the Kasturirangan Report (KR). The KR merely diluted the recommendations of the Gadgil report and pushed the proposal to preserve 37% of the region as an ESA (Ecologically Sensitive Area). This further antagonised the Church and they toughened their stand. In November 2013, a pastoral letter issued by Mar Mathew Anikkuzhikkattil, Bishop of the Idukki diocese of the Syro-Malabar Church, was read out after a Sunday mass in all the parishes under the diocese. It was a call to action asking farmers and inhabitants to protest against the report, or else it would result in them being evicted from their agricultural lands. The Church also decided to politicize the issue and a delegation of the church leaders from Kerala met with Sonia Gandhi in Delhi, who in turn assured them that their concerns would be addressed.

Regardless of the lack of veracity of their claims, the Church continued its fear mongering about a ‘ban on farming’ by both reports. Nowhere did the reports recommend a ban on agriculture in either Zone 1, 2 or 3, but only suggested cultivation shifts away from inorganic (pesticide use) to organic farming. The report also stated that cultivation of genetically modified crops should cease across the Western Ghats, and this recommendation reflected the interests of the locals, tribals, and farmers in the region. There was no such proposal made for the relocation of any farmers or tribes from the forest areas, instead government schemes were recommended to provide financial assistance for farmers that were willing to take up traditional organic farming. Amid strong protests and hartals by the Church, in 2014, a sitting Member of Parliament from Idukki, Mr. PT Thomas, a vehement supporter of the Western Ghats reports, was even denied a ticket to contest the upcoming Lok Sabha elections (though he had won in 2009 by more than 74,000 votes). In an interview with Down to Earth magazine, he said – “It could be because of my stand on the conservation of the Western Ghats. I don’t see any other reason… My stand upset the Idukki dioceses of the Syro Malabar Catholic Church. The Idukki Bishop had openly opposed my candidature. The church has a good say in Idukki and it has been a supporter of our political front. The Church has been campaigning against the Kasturirangan and Gadgil committee reports. Agitations against the reports in Idukki are led by High Range Protection Council which is headed by Sebastian Kochupurakkal, a priest.”

Unfortunately, an already uphill battle to protect and preserve the Western Ghats was politicized beyond repair. Those who advocate for the uncompromising protection of the Western Ghats are neither idealists nor anti-development, rather a rare breed that recognizes the importance of preserving this rich and biodiverse ecosystem, and perhaps feel a connection with nature that is as old as time.

Conclusion

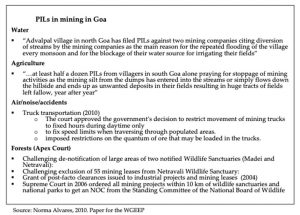

The Gadgil report recommends to put all decisions related to the inclusion of any areas into the ESA zones in the hands of local communities – a provision taken advantage of by 25 Gram Sabhas in the Sindhudurg District of Maharashtra. These Gram Sabhas had requested the Gadgil Committee to include their villages in Zone 1, as that would prevent any new mining activity from being allowed in their villages. A proper understanding of the GR shows that if implemented, it would help preserve the Ghats from industrial exploitation & pollution and conserve water resources, especially ground water, and therefore benefit those living in the region for generations to come. GR recommended that water courses, water bodies, special habitats, geological formations, biodiversity rich areas, and sacred groves remain as no-go areas for industrial or any developmental projects. The text-box below (taken from the report) details two PILs filed in Goa against mining companies whose indiscriminate activities resulted in change of the course of river streams, resulting in repeated flooding villages and irrigation issues.

Kerala has excluded the entire area recommended by the Kasturirangan Committee by setting up its own committee. Goa and Maharashtra have sought to exclude large number of villages from the protection of being in Ecozones. Karnataka has taken a decision not to accept the Kasturirangan report. The result is that the region, recognized as one of the world’s 8 remaining biodiversity hotspots, does not have the protection that is imperative, and which was sought even by the MOEF&CC when it set up the WGEEP a decade ago. States, backed by powerful lobby groups, continually request the Centre to relax the restrictions on areas that fall under eco-sensitive zones and audaciously permit mining activity in the Western Ghats.

India has been experiencing erratic weather and irregular monsoons since past few years and with every year, IMD’s failure at predictions and losses faced by the agricultural sector apart from the loss of lives and infra in afflicted regions has been rising. Anthropogenic disturbances including landscape alterations and improper land-use practices in the Sahyadri hills, hindrance of lower order streams/springs, vertical cutting, intensive quarrying, unscientific rain pits & man-made structures together with erratic rainfall triggered major and minor landslides in various segments of Western Ghats. Sadly, there has been no recall of what the Gadgil report had warned of. Thousands have lost lives, lakhs have been displaced and yet, neither report is being discussed and reconsidered.

The rejection of the reports and the steps needed to conserve the venerated Sahyadri is a blot on our civilization. In the past, indigenous cultures did not have any complex legislations but instinctively lived harmoniously with nature. Today, most rivers flowing through the Western Ghats are either dammed or diverted, with many west-flowing rivers having been diverted from their natural course due to man-made causes. Sacred groves in the region that were once numerous, have dwindled drastically in number.

For the precious Western Ghats to be truly revived and saved from further wanton destruction, we must rethink current paradigms and push to formulate developmental models and policies that are compatible with and reflect our ancient culture’s inherent reverence for nature. Hindu cultural and traditional practices that have the potential to rejuvenate man’s close relationship with the sanctity of nature must be revived and promoted, instead of blindly adopting the western worldview that treats nature as but a resource to be exploited to generate wealth in pursuit of “development”.